After last year’s disastrous hurricane season that included storms like Harvey, Irma and Maria, the U.S. probably won’t see much of a hurricane reprieve this year, according to forecasters from the Colorado State University Tropical Meteorology Project.

The 2018 Atlantic hurricane season forecast released Thursday from Colorado State University calls for the number of named storms and hurricanes to be slightly above historical averages, but less than last year.

The group led by Dr. Phil Klotzbach calls for another busy season with a total of 14 named storms, seven hurricanes and three major hurricanes.

This is just above the 30-year average of 12 named storms, six hurricanes and two major hurricanes. A major hurricane is one that is Category 3 or stronger on the Saffir-Simpson Hurricane Wind Scale.

Though the official Atlantic hurricane season runs from June through November, occasionally we can see storms form outside those months, as happened last season with April’s Tropical Storm Arlene.

The CSU outlook is based more than 30 years of statistical predictors, combined with seasons exhibiting similar features of sea-level pressure and sea-surface temperatures in the Atlantic and eastern Pacific Oceans.

Here are three questions what this outlook means.

Q: What Does This Mean For the U.S.?

There is no strong correlation between the number of storms or hurricanes and U.S. landfalls in any given season. One or more of the 14 named storms forecast to develop this season could hit the U.S., or none at all. Therefore, residents of the coastal United States should prepare each year no matter the forecast.

A couple of classic examples of why you need to be prepared each year occurred in 1992 and 1983.

The 1992 season produced only six named storms and one subtropical storm. However, one of those named storms was Hurricane Andrew, which devastated South Florida as a Category 5 hurricane.

In 1983 there were only four named storms, but one of them was Alicia. The Category 3 hurricane hit the Houston-Galveston area and caused almost as many direct fatalities there as Andrew did in South Florida.

In contrast, the 2010 season was active. There were 19 named storms and 12 hurricanes that formed in the Atlantic Basin.

Despite the large number of storms that year, not a single hurricane and only one tropical storm made landfall in the United States.

In other words, a season can deliver many storms, but have little impact, or deliver few storms and have one or more hitting the U.S. coast with major impact.

The U.S. averages one to two hurricane landfalls each season, according to NOAA’s Hurricane Research Division statistics.

In 2017, seven named storms impacted the U.S. coast, including Puerto Rico, most notably hurricanes Harvey, Irma and Maria, which battered Texas, Florida and Puerto Rico, respectively.

In 2016, five named storms impacted the Southeast U.S. coast, most notably the powerful scraping of the coast from Hurricane Matthew, and its subsequent inland rainfall flooding.

Before that, the number of U.S. landfalls had been well below average over the previous 10 years.

The 10-year running total of U.S. hurricane landfalls from 2006 through 2015 was seven, according to Alex Lamers, a meteorologist with The National Weather Service. This was a record low for any 10-year period dating to 1850, considerably lower than the average of 17 per 10-year period dating to 1850, Lamers added.

Bottom line: It’s impossible to know for certain if a U.S. hurricane strike, or multiple strikes, will occur this season. Keep in mind, however, that even a weak tropical storm hitting the U.S. can cause major impacts, particularly if it moves slowly, resulting in flooding rainfall.

Q: Will El Niño or La Niña play a role?

The odds are increasingly in favor for the development of a neutral state of El Niño or a weak El Niño by the heart of the hurricane season. In other words, near average or slightly warmer than average water temperatures in the eastern Pacific are anticipated.

El Niño, or the periodic warming of the central and eastern equatorial waters of the Pacific Ocean, tends to produce areas of stronger wind shear (the change in wind speed with height) and sinking air in parts of the Atlantic Basin that is hostile to either the development or maintenance of tropical cyclones.

The chances of El Niño development climb toward the end of the season, according to the Climate Prediction Center, but neutral conditions are most likely during the peak of hurricane season, which occurs in September.

Klotzbach noted in the outlook that there is considerable uncertainty regarding the future state of El Niño. In fact, “the latest plume of ENSO (El Niño-Southern Oscillation) predictions from a large number of statistical and dynamical models shows a large spread by the peak of the Atlantic hurricane season in August-October.”

However, based on the current information, Klotzbach says that the “best estimate is that we will likely have neutral ENSO conditions by the peak of the Atlantic hurricane season.”

ENSO conditions will need to be closely monitored over the next few months.

Q: Any Other Factors in Play?

Water temperatures in the Atlantic have a much more direct role in tropical cyclone development on our side of the continent.

The current water temperatures across the North Atlantic basin show cooler-than-average water temperatures in the far North Atlantic and in the eastern tropical Atlantic and warmer-than-average water temperatures off the East Coast of the U.S., Klotzbach points out.

Since early March there has been some slight anomalous warming across the eastern and central tropical Atlantic, Klotzbach notes. It remains a big question of what water temperatures will be in the North Atlantic during the peak of hurricane season.

Remember, however, that it isn’t the anomalies that allow hurricanes to intensify, but rather the actual heat of the oceans.

Water temperatures of 80 degrees or higher are generally supportive of tropical storm and hurricane formation and development.

Much of the tropics stay at or above this temperature for most of the year.

So why bring it up if favorable conditions are always around?

If temperatures in the MDR are warmer than average, we often get more than the average number of tropical storms and hurricanes from this region. Conversely, below average ocean temperatures can lead to less tropical storms than if waters were warmer.

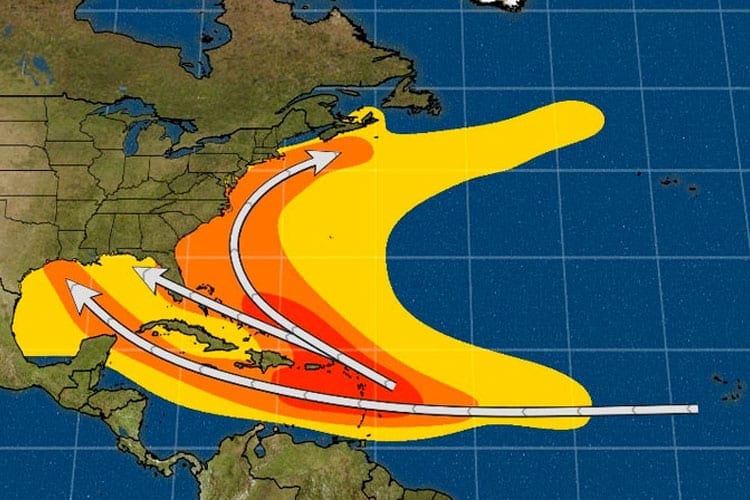

Another aspect that we must keep in mind is that warmer waters in the MDR allows tropical waves, the formative engines that can become tropical storms, to get closer to the Caribbean and United States.

Another factor to consider is the end of the positive phase of the Atlantic Multidecadal Oscillation (AMO). This is a climate cycle that lasts roughly 50-80 years, with about half of that period seeing increased hurricane activity while the other half sees decreased activity.

The current upward swing began in 1995, and the index that measures AMO has been in the cold or decreased phase in recent years and is near its long-term average.

The AMO only has high-level effects on the tropics, and any effects from the cycle will need to be researched after the season is over.

The 2013 and 2014 seasons featured prohibitive dry air and/or wind shear during a significant part of the season, but El Niño was nowhere to be found.

This was the second April outlook issued since the passing of Dr. William Gray, noted hurricane researcher and emeritus professor of atmospheric science at Colorado State University.

Gray, who died in April of 2016, was the creator of the yearly Atlantic hurricane season outlooks, which have been published every year since 1984. He developed the parameters for these outlooks in the late 1960s, which was considered ground-breaking research at that time.

View the original article here.